10.3 Psychosocial Changes in Late Adulthood

What are psychosocial changes in late adulthood?

Our ideas about aging, and what it means to be over 50, over 60, or even over 90, seem to be stuck somewhere back in the middle of the 20th century. We still consider 65 as the standard retirement age, and we expect everyone to start slowing down and moving aside for the next generation as their age passes the half-century mark. In this section, we explore psychosocial developmental theories, including Erik Erikson’s theory on psychosocial development in late adulthood, and we look at aging as it relates to work, retirement, and leisure activities for older adults. We’ll also examine ways in which people are productive in late adulthood.

Learning Objectives

- Describe theories related to late adulthood, including Erikson’s psychosocial stage of integrity vs. despair

- Describe examples of productivity in late adulthood

- Describe attitudes about aging

- Examine family relationships during late adulthood (grandparenting, marriage, divorce, widowhood, traditional and non-traditional roles; co-habitation, LGBTQ+)

Psychosocial Development in Late Adulthood

Erikson’s Theory

| Table 1. Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Development | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Age (years) | Developmental Task | Description |

| 1 | 0–1 | Trust vs. mistrust | Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

| 2 | 1–3 | Autonomy vs. shame/doubt | Develop a sense of independence in many tasks |

| 3 | 3–6 | Initiative vs. guilt | Take initiative on some activities—may develop guilt when unsuccessful or boundaries overstepped |

| 4 | 7–11 | Industry vs. inferiority | Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

| 5 | 12–18 | Identity vs. confusion | Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

| 6 | 19–29 | Intimacy vs. isolation | Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

| 7 | 30–64 | Generativity vs. stagnation | Contribute to society and be part of a family |

| 8 | 65– | Integrity vs. despair | Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions |

Erikson: Integrity vs. Despair

From the mid-60s to the end of life, we are in the period of development known as late adulthood. Erikson’s task at this stage is called integrity vs. despair. He said that people in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity, and they can look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” and “could have” been. They may face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair.

As a person grows older and enters into the retirement years, the pace of life and productivity tend to slow down, granting a person time for reflection upon their life. This process of reflecting on and evaluating your life, either orally or in writing, has been called a life review and been found to benefit older adult well-being (Butler, 1963; Haber, 2006).

They may ask the existential question, “It is okay to have been me?” If someone sees themselves as having lived a successful life, they may see it as one filled with productivity, or according to Erik Erikson, integrity. Here, integrity is said to consist of the ability to look back on one’s life with a feeling of satisfaction, peace, and gratitude for all that has been given and received. Erikson (1959/1980) notes in this regard:

“The possessor of integrity is ready to defend the dignity of his own lifestyle against all physical and economic treats. For he knows that an individual life is the accidental coincidence of but one life cycle within but one segment of history; and that for him all human integrity stands and falls with the one style of integrity of which he partakes.” (Erikson, 1959/1980, p. 104)

Thus, persons derive a sense of meaning (i.e., integrity) through careful review of how their lives have been lived (Krause, 2012). Ideally, however, integrity does not stop here but rather continues to evolve into the virtue of wisdom. According to Erikson, this is the goal during this stage of life. If a person sees their life as unproductive, or feel that they did not accomplish their life goals, they may become dissatisfied with life and develop what Erikson calls despair, often leading to depression and hopelessness. This stage can occur out of the sequence when an individual feels they are near the end of their life (such as when receiving a terminal disease diagnosis).

Erikson’s Ninth Stage

Erikson collaborated with his wife, Joan, through much of his work on psychosocial development. In the Erikson’s older years, they re-examined the eight stages and created additional thoughts about how development evolves during a person’s 80s and 90s. After Erik Erikson passed away in 1994, Joan published a chapter on the ninth stage of development, in which she proposed (from her own experiences and Erik’s notes) that older adults revisit the previous eight stages and deal with the previous conflicts in new ways, as they cope with the physical and social changes of growing old. In the first eight stages, all of the conflicts are presented in a syntonic-dystonic matter, meaning that the first term listed in the conflict is the positive, sought-after achievement and the second term is the less-desirable goal (ie. trust is more desirable than mistrust and integrity is more desirable than despair). During the ninth stage, Erikson argues that the dystonic, or less desirable outcome, comes to take precedence again. For example, an older adult may become mistrustful (trust vs. mistrust), feel more guilt about not having the abilities to do what they once did (initiative vs. guilt), feel less competent compared with others (industry vs. inferiority) lose a sense of identity as they become dependent on others (identity vs. role confusion), become increasingly isolated (intimacy vs. isolation), feel that they have less to offer society (generativity vs. stagnation). The Erikson’s found that those who successfully come to terms with these changes and adjustments in later life make headway towards gerotrancendence, a term coined by gerontologist Lars Tornstam to represent a greater awareness of one’s own life and connection to the universe, increased ties to the past, and a positive, transcendent, perspective about life.

Activity Theory

Developed by Havighurst and Albrecht in 1953, activity theory addresses the issue of how persons can best adjust to the changing circumstances of old age–e.g., retirement, illness, loss of friends and loved ones through death, etc. In addressing this issue they recommend that older adults involve themselves in voluntary and leisure organizations, child care, and other forms of social interaction. Activity theory thus strongly supports the avoidance of a sedentary lifestyle and considers it essential to health and happiness that the older person remains active physically and socially. In other words, the more active older adults are the more stable and positive their self-concept will be, which will then lead to greater life satisfaction and higher morale (Havighurst & Albrecht, 1953). Activity theory suggests that many people are barred from meaningful experiences as they age, but older adults who continue to want to remain active can work toward replacing opportunities lost with new ones.

Disengagement Theory

Disengagement theory, developed by Cumming and Henry in the 1950s, in contrast to activity theory, emphasizes that older adults should not be discouraged from following their inclination towards solitude and greater inactivity. While not completely discounting the importance of exercise and social activity for the upkeep of physical health and personal well being, disengagement theory is opposed to artificially keeping the older person so busy with external activities that they have no time for contemplation and reflection (Cumming & Henry, 1961). In other words, disengagement theory posits that older adults in all societies undergo a process of adjustment which involves leaving their former public and professional roles and narrowing their social horizon to the smaller circle of family and friends. This process enables the older person to die more peacefully, without the stress and distractions that come with a more socially involved life. The theory suggests that during late adulthood, the individual and society mutually withdraw. Older people become more isolated from others and less concerned or involved with life in general. This once-popular theory is now criticized as being ageist and used in order to justify treating older adults as second class citizens.

Continuity Theory

Continuity theory suggests as people age, they continue to view the self in much the same way as they did when they were younger. An older person’s approach to problems, goals, and situations is much the same as it was when they were younger. They are the same individuals, but simply in older bodies. Consequently, older adults continue to maintain their identity even as they give up previous roles. For example, a retired Coast Guard commander attends reunions with shipmates, stays interested in new technology for home use, is meticulous in the jobs he does for friends or at church, and displays mementos from his experiences on the ship. He is able to maintain a sense of self as a result. People do not give up who they are as they age. Hopefully, they are able to share these aspects of their identity with others throughout life. Focusing on what a person can do and pursuing those interests and activities is one way to optimize and maintain self-identity.

Generativity in Late Adulthood

People in late adulthood continue to be productive in many ways. These include work, education, volunteering, family life, and intimate relationships. Older adults also experience generativity (recall Erikson’s previous stage of generativity vs. stagnation) through voting, forming, and helping social institutions like community centers, churches, and schools. Psychoanalyst Erik Erikson wrote, “I am what survives me.”

Productivity in Work

Some continue to be productive in work. Mandatory retirement is now illegal in the United States. However, many do choose retirement by age 65 and most leave work by choice. Those who do leave by choice adjust to retirement more easily. Chances are, they have prepared for a smoother transition by gradually giving more attention to an avocation or interest as they approach retirement. And they are more likely to be financially ready to retire. Those who must leave abruptly for health reasons or because of layoffs or downsizing have a more difficult time adjusting to their new circumstances. Men, especially, can find unexpected retirement difficult. Women may feel less of an identity loss after retirement because much of their identity may have come from family roles as well. But women tend to have poorer retirement funds accumulated from work and if they take their retirement funds in a lump sum (be that from their own or from a deceased husband’s funds), are more at risk of outliving those funds. Women need better financial retirement planning.

Sixteen percent of adults over 65 were in the labor force in 2008 (U. S. Census Bureau, 2011). Globally, 6.2 percent are in the labor force and this number is expected to reach 10.1 million by 2016. Many adults 65 and older continue to work either full-time or part-time either for income or pleasure or both. In 2003, 39 percent of full-time workers over 55 were women over the age of 70; 53 percent were men over 70. This increase in numbers of older adults is likely to mean that more will continue to part of the workforce in years to come (He et al., article, U. S. Census, 2005).

Volunteering: Face-to-face and Virtually

About 40 percent of older adults are involved in some type of structured, face-to-face, volunteer work. But many older adults, about 60 percent, engage in a sort of informal type of volunteerism helping out neighbors or friends rather than working in an organization (Berger, 2005). They may help a friend by taking them somewhere or shopping for them, etc. Some do participate in organized volunteer programs but interestingly enough, those who do tend to work part-time as well. Those who retire and do not work are less likely to feel that they have a contribution to make. (It’s as if when one gets used to staying at home, their confidence to go out into the world diminishes.) And those who have recently retired are more likely to volunteer than those over 75 years of age.

New opportunities exist for older adults to serve as virtual volunteers by dialoguing online with others from around their world and sharing their support, interests, and expertise. According to an article from AARP (American Association of Retired Persons), virtual volunteerism has increased from 3,000 in 1998 to over 40,000 participants in 2005. These volunteer opportunities range from helping teens with their writing to communicating with ‘neighbors’ in villages of developing countries. Virtual volunteering is available to those who cannot engage in face-to-face interactions and opens up a new world of possibilities and ways to connect, maintain identity, and be productive (Uscher, 2006).

Education

Twenty-seven percent of people over 65 have a bachelor’s or higher degree. And over 7 million people over 65 take adult education courses (U. S. Census Bureau, 2015). Lifelong learning through continuing education programs on college campuses or programs known as “Elderhostels” which allow older adults to travel abroad, live on campus and study provide enriching experiences. Academic courses as well as practical skills such as computer classes, foreign languages, budgeting, and holistic medicines are among the courses offered. Older adults who have higher levels of education are more likely to take continuing education. But offering more educational experiences to a diverse group of older adults, including those who are institutionalized in nursing homes, can enhance the quality of life.

Religious Activities

People tend to become more involved in prayer and religious activities as they age. This provides a social network as well as a belief system that can combat the fear of death. Religious activities provide a focus for volunteerism and other activities as well. For example, one elderly woman prides herself on knitting prayer shawls that are given to those who are sick. Another serves on the altar guild and is responsible for keeping robes and linens clean and ready for communion.

Political Activism

The elderly are very politically active. They have high rates of voting and engage in letter writing to Congress on issues that not only affect them but on a wide range of domestic and foreign concerns. In the past three presidential elections, over 70 percent of people 65 and older showed up at the polls to vote (U. S. Census Bureau).

Attitudes about Aging

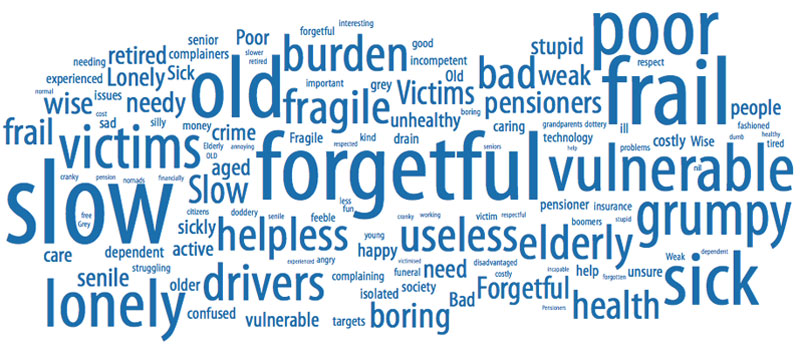

Stereotypes about people in late adulthood lead many to assume that aging automatically brings poor health and mental decline. These stereotypes are reflected in everyday conversations, the media, and even in greeting cards (Overstreet, 2006).

Of course, these cards are made because they are popular. Age is not revered in the United States, and so laughing about getting older is one way to get relief. The attitudes above are examples of ageism, prejudice based on age. Ageism is prejudice and discrimination that is directed at older people. This view suggests that older people are less in command of their mental faculties. Older people are viewed more negatively than younger people on a variety of traits, particularly those relating to general competence and attractiveness. Stereotypes such as these can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy in which beliefs about one’s ability results in actions that make it come true.

Ageism is a modern and predominately western cultural phenomenon—in the American colonial period, long life was an indication of virtue, and Asian and Native American societies view older people as wise, storehouses of information about the past, and deserving of respect. Many preindustrial societies observed gerontocracy, a type of social structure wherein the power is held by a society’s oldest members. In some countries today, the elderly still have influence and power and their vast knowledge is respected, but this reverence has decreased in many places due to social factors. A positive, optimistic outlook about aging and the impact one can have on improving health is essential to health and longevity. Removing societal stereotypes about aging and helping older adults reject those notions of aging is another way to promote health in older populations.

In addition to ageism, racism is yet another concern for minority populations as they age. The number of blacks above the age of 65 is projected to grow from around 4 million now to 12 million by 2060. Racism towards blacks and other minorities throughout the lifetime results in many older minorities having fewer resources, more chronic health conditions, and significant health disparities when compared to older white Americans. Racism towards older adults from diverse backgrounds has resulted in them having limited access to community resources such as grocery stores, housing, health care providers, and transportation.

Elderly Abuse

There are different types of elder abuse, including physical, emotional, sexual, financial, and neglect (Storey, 2020). Nursing homes have been publicized as places where older adults are at risk of abuse. However, older adults are more frequently abused by family members. When abuse occurs in nursing homes, it is more often found in facilities that are run down and understaffed. The most commonly reported type of abuse was emotional, followed by neglect, and financial abuse (Brijoux et al., 2021). Victims are typically socially isolated. Caregivers are often overwhelmed and lack adequate support themselves. Victims are usually frail or impaired, and perpetrators are usually dependent on the victims for support (Ho et al., 2017). Abuse tends to begin slowly and build over time. Prosecuting a family member who has financially abused a parent is very difficult. The victim may be reluctant to press charges, and the court dockets are often very full resulting in long waits before a case is heard.

Current research indicates that at least 1 in 10, or approximately 4.3 million, older Americans are affected by at least one form of abuse per year (Roberto, 2016). Those between 60 and 69 years of age are more susceptible than those older. This may be because younger older adults more often live with adult children or a spouse, two groups with the most likely abusers. Cognitive impairment, including confusion and communication deficits, is the greatest risk factor for elder abuse, while a decline in overall health resulting in greater dependency on others is another. Having a disability also places an older person at a higher risk for abuse (Youdin, 2016). Definitions of abuse of older people typically recognize five types of abuse as shown in the following table.

| Type | Description |

| Physical Abuse | Physical force resulting in injury, pain, or impairment |

| Sexual Abuse | Nonconsensual sexual contact |

| Psychological and Emotional Abuse | Infliction of distress through verbal or nonverbal acts such as yelling, threatening, or isolating |

| Financial Abuse and Exploitation | Improper use of an older person’s finances, property, or assets |

| Neglect and Abandonment | Intentional or unintentional refusal or failure to fulfill caregiving duties to an older person |

Consequences of abuse of older people are significant and include injuries, new or exacerbated health conditions, hospitalizations, premature institutionalization, and early death (Roberto, 2016). Psychological and emotional abuse is considered the most common form, even though it is underreported and may go unrecognized by the older person. Continual emotional mistreatment is very damaging as it becomes internalized and results in late-life emotional problems and impairment. Financial abuse and exploitation is increasing and costs older people nearly 3 billion dollars per year (Lichtenberg, 2016). Financial abuse is the second most common form after emotional abuse, and affects approximately 5% of elders. Abuse and neglect occurring in a nursing home is estimated to be 25% - 30% (Youdin, 2016). Abuse of nursing home residents is more often found in facilities that are run down and understaffed.

Older women are more likely to be victims than men, and one reason is due to women living longer. Additionally, a family history of violence makes older women more vulnerable, especially for physical and sexual abuse (Acierno et al., 2010). However, Kosberg (2014) found that men were less likely to report abuse. Recent research indicated no differences among ethnic groups in abuse prevalence, however, cultural norms regarding what constitutes abuse differ based on ethnicity. For example, Dakin and Pearlmutter found that working class White women did not consider verbal abuse to be abusive, and higher socioeconomic status African American and White women did not consider financial abuse to be abusive (as cited in Roberto, 2016, p. 304).

Perpetrators of abuse are typically family members and include spouses/partners and older children (Roberto, 2016). Children who are abusive tend to be dependent on their parents for financial, housing, and emotional support. Substance use, mental illness, and chronic unemployment increase dependency on parents, which can then increase the possibility of abuse. Prosecuting a family member who has financially abused a parent is very difficult. The victim may be reluctant to press charges and the court dockets are often very full resulting in long waits before a case is heard. According to Tanne, family members abandoning older family members with severe disabilities in emergency rooms is a growing problem as an estimated 100,000 are dumped each year (as cited in Berk, 2007). Paid caregivers and professionals trusted to make decisions on behalf of an older person, such as guardians and lawyers, also perpetuate abuse. When older people have social support and are engaged with others, they are less likely to suffer abuse. In other words it is the marginalization that older people experience that makes them vulnerable to abuse, and it is our responsibility as members of a just society to create policies that keep us all as full participants in society through education, work, recreation, healthcare throughout life.

There is a need for more research on effective prevention strategies (Pillemer et al., 2016). Providing more help and training for caregivers is promising. Money management programs may help reduce risk of financial abuse. Instituting helplines can increase awareness of a problem that is often under-reported. Coordination among community partners, including criminal justice, health care, housing, victim services to form multidisciplinary teams is one of the most promising approaches.

Relationships in Late Adulthood

During late adulthood, many people find that their relationships with their adult children, siblings, spouses, or life partners change. Roles may also change, as many are grandparents or great-grandparents, caregivers to even older parents or spouses, or receivers of care in a nursing home or other care facility.

Grandparenting

It has become increasingly common for grandparents to live with and raise their grandchildren, or also to move back in with adult children in their later years. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there were 2.7 million grandparents raising their grandchildren in 2009. The dramatic increase in grandparent-headed households has been attributed to many factors including parental substance abuse.

Grandparenting typically begins in midlife rather than late adulthood, but because people are living longer, they can anticipate being grandparents for longer periods of time. Cherlin and Furstenberg (1986) describe three styles of grandparents:

1. Remote: These grandparents rarely see their grandchildren. Usually, they live far away from their grandchildren but may also have a distant relationship. Contact is typically made on special occasions such as holidays or birthdays. Thirty percent of the grandparents studied by Cherlin and Furstenberg were remote.

2. Companionate Grandparents: Fifty-five percent of grandparents studied were described as companionate. These grandparents do things with the grandchild but have little authority or control over them. They prefer to spend time with them without interfering in parenting. They are more like friends to their grandchildren.

3. Involved Grandparents: Fifteen percent of grandparents were described as involved. These grandparents take a very active role in their grandchild’s life. The grandchildren might even live with the grandparent. The involved grandparent is one who has frequent contact with and authority over the grandchild.

An increasing number of grandparents are raising grandchildren today. Issues such as custody, visitation, and continued contact between grandparents and grandchildren after parental divorce are contemporary concerns.

Marriage and Divorce

Most males and females aged 65 and older had been married at some point in their lives. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey, among the population 65 and older, males were significantly more likely to be married (70 percent) compared with females (44 percent) in the same age group. Even at the oldest age group, 85 and older, 54 percent of males were still married compared with 15 percent of females.

Twelve percent of older men and 15% percent of older women have been divorced and about 6 percent of older adults have never married. Many married couples feel their marriage has improved with time and the emotional intensity and level of conflict that might have been experienced earlier, has declined. This is not to say that bad marriages become good ones over the years, but that those marriages that were very conflict-ridden may no longer be together, and that many of the disagreements couples might have had earlier in their marriages may no longer be concerns. Successful couples communicate effectively, manage their emotions, and learn how to disagree without showing contempt for their partner (Gottman & Gottman, 2017). As couples age, children have grown and the division of labor in the home has probably been established. Men tend to report being satisfied with marriage more than do women. Women are more likely to complain about caring for a spouse who is ill or accommodating a retired husband and planning activities. Older couples continue to engage in sexual activity, but with less focus on intercourse and more on cuddling, caressing, and oral sex (Carroll, 2007).

Divorce after long-term marriage does occur, but is not as common as earlier divorces, despite rising divorce rates for those above age 65. Older adults who have been divorced since midlife tend to have settled into comfortable lives and, if they have raised children, to be proud of their accomplishments as single parents. Remarriage is also on the rise for older adults; in 2014, 50% of adults ages 65 and older had remarried, up from 34% in 1960. Men are also more likely to remarry than women.

Widowhood

With increasing age, women were less likely to be married or divorced but more likely to be widowed, reflecting a longer life expectancy relative to men. About 2 out of 10 women aged 65 to 74 were widowed compared with 4 out of 10 women aged 75 to 84 and 7 out of 10 women 85 and older. More than twice as many women 85 and older were widowed (72 percent) compared to men of the same age (35 percent). The death of a spouse is one of life’s most disruptive experiences. It is especially hard for men who lose their wives. Often widowers do not have a network of friends or family members to fall back on and may have difficulty expressing their emotions to facilitate grief. Also, they may have been very dependent on their mates for routine tasks such as cooking, cleaning, etc.

Widows may have less difficulty because they do have a social network and can take care of their own daily needs. They may have more difficulty financially if their husbands have handled all the finances in the past. They are much less likely to remarry because many do not wish to and because there are fewer men available. At 65, there are 73 men to every 100 women. The sex ratio becomes even further imbalanced at 85 with 48 men to every 100 women (U. S. Census Bureau, 2011).

Loneliness or solitude?

Loneliness is a discrepancy between the social contact a person has and the contacts a person wants (Brehm et al., 2002). It can result from social or emotional isolation. Women tend to experience loneliness as a result of social isolation; men from emotional isolation. Loneliness can be accompanied by a lack of self-worth, impatience, desperation, and depression. This can lead to suicide, particularly in older, white men who have the highest suicide rates of any age group; higher than Blacks, and higher than for females. Rates of suicide continue to climb and peaks in males after age 85 (National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, 2002).

Being alone does not always result in loneliness. For some, it means solitude. Solitude involves gaining self-awareness, taking care of the self, being comfortable alone, and pursuing one’s interests (Brehm et al., 2002).

Couples who remarry after midlife, tend to be happier in their marriages than in their first marriage. These partners are likely to be more financially independent, have children who are grown, and enjoy a greater emotional wisdom that comes with experience.

Single, Cohabiting, and Remarried Older Adults

About 6 percent of adults never marry. Many have long-term relationships, however. The never-married tend to be very involved in family and caregiving and do not appear to be particularly unhappy during late adulthood, especially if they have a healthy network of friends. Friendships tend to be an important influence on life satisfaction during late adulthood. Friends may be more influential than family members for many older adults. According to socioemotional selectivity theory, older adults become more selective in their friendships than when they were younger (Carstensen et al., 2003). Friendships are not formed in order to enhance status or careers and may be based purely on a sense of connection or the enjoyment of being together. Most elderly people have at least one close friend. These friends may provide emotional as well as physical support. Being able to talk with friends and rely on others is very important during this stage of life.

About 4 percent of older couples chose cohabitation over marriage (Chevan, 1996). The Pew Research Center reported in 2017 that the number of cohabiters over age 50 rose to 4 million from 2.3 million over the decade, and found the number over age 65 doubled to about 900,000. As discussed in our lesson on early adulthood, these couples may prefer cohabitation for financial reasons, may be same-sex couples who cannot legally marry, or couples who do not want to marry because of previous dissatisfaction with marital relationships.

Elderly and LBGTQ+

There has been a growth of interest in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) aging in recent years. Many retirement issues for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) and intersex people are unique from their non-LGBTI counterparts and these populations often have to take extra steps addressing their employment, health, legal, and housing concerns to ensure their needs are met. Throughout the United States, there are 1.5 million adults over the age of 65 who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, and two million people above the age of 50 who identify as such. That number is expected to double by 2030, as estimated in a study done by the Institute for Multigenerational Health at the University of Washington. While LGBTQ+ people have increasingly become more visible and accepted into mainstream cultures, LGBTQ+ elders and retirees are still considered a newer phenomenon, which creates both challenges and opportunities as they redefine some commonly held beliefs about aging.

LGBTQ+ individuals are less likely to have strong family support systems in place to have relatives to care for them during aging. They are twice as likely to enter old age living as a single person, and two and a half times more likely to live alone. Because institutionalized homophobia, as well as cultural discrimination and harassment, still exist, they are less likely to access health care, housing, or social services or when they do, find the experience stressful or demeaning. Joel Ginsberg, executive director of the Gay Lesbian Medical Association, asserts “only by pursuing both strategies, encouraging institutional change and encouraging…and empowering individuals to ask for what they want will we end up with quality care for LGBT people.”

These older adults have concerns over health insurance, being able to share living quarters in nursing homes, and assisted living residences where staff members tend not to be accepting of homosexuality and bisexuality. SAGE (Senior Action in a Gay Environment) is an advocacy group working on remedying these concerns. Same-sex couples who have endured prejudice and discrimination through the years and can rely upon one another continue to have support through late adulthood.

Older Adults, Caregiving, and Long-Term Care

Older adults do not typically relocate far from their previous places of residence during late adulthood. A minority lives in planned retirement communities that require residents to be of a certain age. However, many older adults live in age-segregated neighborhoods that have become segregated as original inhabitants have aged and children have moved on. A major concern in future city planning and development will be whether older adults wish to live in age-integrated or age-segregated communities.

Over 60 million Americans, or 19% of the population, lived in multigenerational households, or homes with at least two adult generations. It has become an ongoing trend for elderly generations to move in and live with their children, as they can give them support and help with everyday living.

Most (70 percent) of older adults who require care receive that care in the home. Most are cared for by their spouse, or by a daughter or daughter-in-law. However, those who are not cared for at home are institutionalized. Assisted living facilities are becoming more common and nursing homes less common. In 2008, 1.6 million out of the total 38.9 million Americans age 65 and older were nursing home residents (U. S. Census Bureau, 2011). Among 65-74, 11 per 1,000 adults aged 65 and older were in nursing homes. That number increases to 182 per 1,000 after age 85. More residents are women than men, and more are Black than white. As the population of those over age 85 continues to increase, more will require nursing home care. Meeting the psychological and social as well as physical needs of nursing home residents is a growing concern. Rather than focusing primarily on food, hygiene, and medication, quality of life for the seniors within these facilities is important. Residents of nursing homes are sometimes stripped of their identity as their personal possessions and reminders of their lives are taken away. A rigid routine in which the residents have little voice can be alienating to anyone, but more so for an older adult. Routines that encourage passivity and dependence can be damaging to self-esteem and lead to further deterioration of health. Greater attention needs to be given to promoting successful aging within institutions.

Conclusion

The period of late adulthood, which starts around age 65, is characterized by great changes and ongoing personal development. Older adults face profound physical, cognitive, and social changes, and many figure out strategies for adjusting to them and successfully cope with old age. In late adulthood, people begin the decline that will be part of their lives until death. The declines in the senses—vision, hearing, taste, and smell—can have major psychological consequences. Most illnesses and diseases of late adulthood are not particular to old age, but the incidences of cancer and heart disease rise with age. People in late adulthood are also more prone to develop arthritis, hypertension, major neurocognitive disorders, and Alzheimer’s disease. Proper diet, exercise, and avoidance of health risks can all lead to overall well-being during old age, and sexuality can continue throughout the lifespan in healthy adults. Thus, many older adults can maintain physical and mental strength until they die, and their social worlds can also remain as vital and active as they want.

Cognitively, we find that older people adjust quite well to the challenges of aging by adopting new strategies for solving problems and compensating for loss of abilities. Although some intellectual abilities gradually decline throughout adulthood, starting at around the age of 25, others stay relatively steady. For example, research shows that while fluid intelligence declines with age, crystallized intelligence remains steady, and may even improve, in late adulthood. Many cognitive abilities can be maintained with stimulation, practice, and motivation. Declines in memory affect mainly episodic memory and short-term memory, or working memory. Explanations of memory changes in old age focus upon environmental factors, information processing declines, and biological factors. Due to this perceived loss of abilities by others, older people are often subject to ageism, or prejudice and discrimination against people based on their age.

Socially, many older adults become adept at coping with the changes in their lives, such as the death of a spouse and retirement from work. Erikson calls older adulthood the integrity vs. despair stage. According to Erikson, individuals in late adulthood engage in looking back over their lives, evaluating their experiences, and coming to terms with decisions. Other theorists focus on the tasks that define late adulthood and suggest that older people can experience liberation and self-regard. Marriages in older adulthood are generally happy, but the many changes in late adulthood can cause stress which may result in divorce. The death of a spouse has major psychological, social, and material effects on the surviving widow and makes the formation and continuation of friendships highly important. Family relationships are a continuing part of most older people’s lives, especially relationships with siblings, children, and grandchildren. Friendships, an important source of social support, are not only valued but needed in late adulthood.

Whether death is caused by genetic programming or by general physical wear-and-tear is an unresolved question. Life expectancy, which has risen for centuries, varies with gender, race, and ethnicity and new approaches to increasing life expectancy is a growing topic of research.

Additional Supplemental Resources

Websites

Classification of Neurocognitive Disorders in DSM-5: A Work in Progress

- This article explains the shift in renaming the term dementia to neurocognitive disorders. The Neurocognitive Disorders Work Group of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) DSM-5 Task Force began work in April 2008 on their task of proposing revisions to the criteria for the disorders referred to in DSM-IV as Delirium, Dementia, Amnestic and Other Cognitive Disorders

- American Society on Aging

- ASA is the go-to source to cultivate leadership, advance knowledge, and strengthen the skills of our members and others who work with and on behalf of older adults.

Videos

- Studying brains as we age

- Learn more about how psychology research is conducted through the work of a neuropsychologist who studies how cultural experiences affect our brains as we age. Closed captioning available.

- Crash Course Video #14 – Remembering and Forgetting

- This video on remembering and forgetting includes information on topics such as implicit and explicit memory, encoding, retrieval, and the misinformation effect. Closed captioning available.

- 57 Years Apart – A Boy And a Man Talk About Life

- We brought together two people with a very large gap of 57 years between them and got them to ask each other questions about life and growing up. Our aim was to see if people from opposing stages of their lives could learn from each other.

- Life Lessons From 100-Year-Olds

- We asked three centenarians what their most valuable life lessons were, and also their regrets. The conversations that followed were remarkable. They talked about the importance of family, people, relationships, and love. Their view on life, as an elderly citizen with a lot of experience, is truly an inspiration and motivation. Enjoy the video!

- What is Alzheimer’s disease? – Ivan Seah Yu Jun

- Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, affecting over 40 million people worldwide. And though it was discovered over a century ago, scientists are still grappling for a cure. Ivan Seah Yu Jun describes how Alzheimer’s affects the brain, shedding light on the different phases of this complicated, destructive disease.

- How Old Are Your Ears? (Hearing Test)

- How high can you hear? Take this ‘test’ to see how old your ears are!

- Life and Death in Assisted Living

- More and more elderly Americans are choosing to spend their later years in assisted living facilities, which have sprung up as an alternative to nursing homes. But is this loosely regulated, multi-billion dollar industry putting seniors at risk? In a major investigation with ProPublica, FRONTLINE examines the operations of the nation’s largest assisted living company, raising questions about the drive for profits and fatal lapses in care.