Chapter 2: Determinants of Health

(World Health Organization, 2017)

Many factors combine together to affect the health of individuals and communities. Whether people are healthy or not, is determined by their circumstances and environment. To a large extent, factors such as where we live, the state of our environment, genetics, our income and education level, and our relationships with friends and family all have considerable impacts on health, whereas the more commonly considered factors such as access and use of health care services often have less of an impact.

The determinants of health include:

- the social and economic environment,

- the physical environment, and

- the person’s individual characteristics and behaviors.

The context of people’s lives determine their health, and so blaming individuals for having poor health or crediting them for good health is inappropriate. Individuals are unlikely to be able to directly control many of the determinants of health. These determinants—or things that make people healthy or not—include the above factors, and many others:

- Income and Social Status: Higher income and social status are linked to better health. The greater the gap between the richest and poorest people, the greater the differences in health.

- Education: Low education levels are linked with poor health, more stress and lower self-confidence.

- Physical Environment: Safe water and clean air, healthy workplaces, safe houses, communities, and roads all contribute to good health.

- Employment and Working Conditions: People in employment are healthier, particularly those who have more control over their working conditions.

- Social Support Networks: Greater support from families, friends, and communities is linked to better health.

- Culture: Customs, traditions, and the beliefs of the family and community all affect health.

- Genetics: Inheritance plays a part in determining lifespan, healthiness, and the likelihood of developing certain illnesses.

- Personal Behavior and Coping Skills: Balanced eating, keeping active, smoking, drinking, and how we deal with life’s stresses and challenges all affect health.

- Health Services: Access and use of services that prevent and treat disease influences health.

- Gender: Men and women suffer from different types of diseases at different ages.

Social Determinants of Health

(World Health Organization, n.d.-b)

The social determinants of health (SDH) are the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. They are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems.

The SDH have an important influence on health inequities - the unfair and avoidable differences in health status seen within and between countries. In countries at all levels of income, health and illness follow a social gradient: the lower the socioeconomic position, the worse the health.

The following list provides examples of the social determinants of health, which can influence health equity in positive and negative ways:

- Income and social protection

- Education

- Unemployment and job insecurity

- Working life conditions

- Food insecurity

- Housing, basic amenities and the environment

- Early childhood development

- Social inclusion and non-discrimination

- Structural conflict

- Access to affordable health services of decent quality

Research shows that the social determinants can be more important than health care or lifestyle choices in influencing health. For example, numerous studies suggest that SDH accounts for between 30-55% of health outcomes. In addition, estimates show that the contribution of sectors outside health to population health outcomes exceeds the contribution from the health sector.

Addressing SDH appropriately is fundamental for improving health and reducing longstanding inequities in health, which requires action by all sectors and civil society.

Adopting a social determinants of health lens to view a health issue also requires looking at three different levels of causes:

| Level of the Cause | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Distal | Cultural, political, and infrastructural causes | Education, income, housing conditions, air quality, access to food and water, road safety |

| Intermediate | Relationships, social contexts | Community factors, including those related to work, school, family, and peer environments |

| Proximal (closest to an individual’s health status) or individual | Behaviors, capabilities, attitudes, and direct biological threats to health | Hygiene habits, exposure to disease vectors that cause diarrhea, dengue, malaria |

At the distal level are the wider circumstances in which people live, including broader cultural values, national or international political forces, laws or policies, or cross-cutting exposures like those related to climate, conflict, or the media. These factors are called distal because they are not directly related to the individual, but rather establish the wider context in which a person lives.

At the intermediate level are factors related to communities, workplaces, schools, or families that define an individual’s more immediate social environments.

Finally, at the proximal level are factors directly related to individuals themselves which impact health, including personal biology, behaviors, capabilities, or attitudes.

Considering the different levels at which determinants operate can help you keep track of a complex array of contributing factors, while also highlighting potential pathways between social exposures and physical health.

(Global Health Education and Learning Incubator at Harvard University, 2018)

In Practice

There are challenges to overcome in implementing action to address health inequities through the social determinants of health. It involves a wide range of stakeholders within and beyond the health sector and all levels of government. In addition, social determinants of health data can be difficult to collect and share.

While the evidence based on the social determinants of health has strengthened during the past decade, the evidence base on what works needs to be strengthened and good practices disseminated effectively.

Three areas for critical action identified in the report of the Global Commission on Social Determinants of Health reflect their importance in tackling inequities in health. These include:

- Improve daily living conditions: The circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work and age;

- Tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money and resources: The structural drivers of those conditions of daily life (for example, macroeconomic and urbanization policies and governance);

- Measure and understand the problem and assess the impact of action: Expand the knowledge base, develop a workforce that is trained in the social determinants of health, and raise public awareness about the social determinants of health.

Scaled up and systematic action is required that is universal but proportionate to the disadvantage across the social gradient. This is necessary for effective delivery to address inequities in health and promote healthier populations.

Health Equity

Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy have increased, but unequally. There remain persistent and widening gaps between those with the best and worst health and well-being.

Poorer populations systematically experience worse health than richer populations. For example:

There is a difference of 18 years of life expectancy between high- and low- income countries;

In 2016, the majority of the 15 million premature deaths due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) occurred in low- and middle-income countries. Relative gaps within countries between poorer and richer subgroups for diseases like cancer have increased in all regions across the world. The under-5 mortality rate is more than eight times higher in Africa than the European region. Within countries, improvements in child health between poorest and richest subgroups have been impaired by slower improvements for poorer subgroups.

Such trends within and between countries are unfair, unjust, and avoidable. Many of these health differences are caused by the decision-making processes, policies, social norms, and structures which exist at all levels in society.

Inequities in health are socially determined, preventing poorer populations from moving up in society and making the most of their potential.

Pursuing health equity means striving for the highest possible standard of health for all people and giving special attention to the needs of those at greatest risk of poor health, based on social conditions.

Action requires not only equitable access to healthcare but also means working outside the healthcare system to address broader social well-being and development.

Health equity is defined as the absence of unfair and avoidable or remediable differences in health among population groups defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically.

Culture and Health

Culture is a social determinant of health that is particularly relevant in the context of global health. Cultural identity influences our food choices and attitudes towards food and body image; whether or not, and for how long women breastfeed their children; hygiene practices; perceptions of illness and what causes them; reactions to illness and when, where, and from whom health services and treatments are pursued; educational pursuits; marital practices and family structure; among many other factors that ultimately influence health (Skolnik, 2021).

An individual’s culture is made up of values, beliefs and traditional practices in their family and social group. Cultural and religious practices often affect health and can vary widely between different groups. Authors Yildiz, Toruner and Altay (Yildiz et al., 2018) give examples of how children’s health is affected by their culture and religion, and offer suggestions on how healthcare providers can work effectively within some of the major cultural groups.

Religious beliefs are a part of an individual’s and group’s culture, and can greatly affect their health. Table 1 shows examples of seven different religions and some of their health-related practices.

Table 1: Religious Beliefs and Healthcare Practices with Impact on Child Health

| Religious Belief | Nutrition | Medical Care |

|---|---|---|

| Buddhism | Avoid overfeeding. Some are vegetarians. The use of alcohol and drugs is inconvenient. | Surgeries are frequently avoided. Cleaning is important. |

| Christian Scientist | Coffee, some tea forms and alcohol use are avoided. | Some drugs and other therapy practices could resist. They accept physical and spiritual treatments. |

| Hinduism | There are many food restrictions. Meat and some food consumption forbidden. | Acceptance of most medical practice/care |

| Islamism | Ingestion of pork and pork products and alcohol forbidden | Treatments are not rejected. The boys are circumcised. |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | Tobacco use is prohibited. Less alcohol can be used. | Usually do not use blood or blood components, Blood volume boosters can be used when no blood is given. |

| Judaism | Some animals’ meat and vegetables are eaten. Shellfish, pork and predators are forbidden to eat. Dairy products are consumed after a few minutes of eating meat. | The boys are circumcised. |

| Roman Catholic | The first Wednesday before Easter is forbidden to consume meat. | Sacred oils are used to treat diseases. |

Table 2 shows practices that health professionals should be aware of, among ten different nationalities and ethnic groups.

Public health professionals need to be conscious of how an individual’s culture is affecting his or her health, and how to best assist and encourage that individual in ways that are appropriate to his or her unique cultural perspective.

Table 2: Health Practices According to Living Region of The Child and Family, Child Family Relations and Ways of Communication

| Nationalities | Healthcare Practices | Children and Family Relations | Communication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africans | Medical practices: Traditional healthcare is prevalent. Traditional practices usually have religious origins that are applied with the traditional physician. Religious practices: Prayers are often used for cure and protection against diseases. | Extended families are found and family bonds are strong. | Non-verbal behavior has a significant place. Lengthy eye contact may be seen as an expression of anger. |

| Chinese | Medical practices: Acupuncture and acupressure, as well as herbal remedies are widely used modes of treatment. | Extended families are found. Children’s behavior reflects the family’s behavior. Dignity, self-assurance, and self-respect of the individual and family are fairly important. | They do not condone open expressions of sentiments. As a sign of respect, they avoid eye contact. |

| Haitians | Nutrition: Food should be able to keep the balance between cold and hot and heavy and light. Religious practices: Prayers are used and religious symbols may be utilized. | Procreation of the family is important. Child has a secondary place in the family hierarchy. | They usually laugh when they fail to understand something. |

| Japanese | Medical practices: Acupuncture, acupressure, massage, moxibustion, kampo medicine, and herbs are used. | There are strong relations between generations. Children’s behavior reflects the family. Children are important for being the posterity. | They easily express their feelings with facial expressions and hand gestures and they are open to communication. |

| Native Americans | Certain diseases are cured with medical methods and certain diseases are cured with traditional methods. | Extended families are found. The elderly are seen as leaders of the family. | Contact is made on a non-verbal basis. Avoiding eye contact is seen as disrespectful. |

| Mexican Americans | Medical practices include herbal methods, rituals, and religious phenomena. Religious practices: Prayer, visiting temples, burning candles, and worship are preferred. Nutrition: Hot or cold food is prohibited. | Family bonds are strong. Extended families are found. Children are highly precious and are loved. | Lengthy eye contact is interpreted as being disrespectful. |

| Vietnamese | Medical practices: There are concerns about touching the patient’s head at examination. Traditional practices prevail. Herbal products, acupuncture, and spiritual practices are used. | Family is a respectable institution. Extended families are found. Children are highly precious. Parents expect respect and obedience from their children. | They may hesitate to ask questions and see it as disrespectful. As a sign of respect, they may avoid eye contact with health professionals. |

| Hispanics | Traditional medical practices such as herbal teas and poultice, as well as prayer are used at treatment of patients. | Family is an important structure. Father is seen as the wisdom, power, and self-assurance of the family. Mother is a caregiver and the decision maker in health issues. | |

| Puerto Ricans | Traditional practices are prevalent at treatment of patients and various herbs are used to improve health. | Extended families are found. Children are precious and are seen as gifts of God. Children are required to respect and obey their parents. | |

| South Asia; Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Maldives | Religious norms are very important. Sacred water is sprinkled around the sickbed and the patient is made to drink the sacred water. | Decisions on the family are taken by the head priest and the family sees death as a social process. Bonds between relatives in the family are strong. | Specific questions may be asked to strengthen communication with the family and the child. |

Cultural Competence and Cultural Humility in Global Health

In global health study and practice, it is common to interact with individuals and communities whose cultures differ from our own. Being able to understand and be sensitive to the influence that culture has on health beliefs, practices, and outcomes is important; however, what is even more critical is being able to develop cultural competence and cultural humility so that it is possible to effectively serve, communicate, and engage with people from all cultural groups and backgrounds in ways that support enhancing their health. This requires an ability to avoid judging another culture from an ethnocentric point of view (through the lens or perspective of our own personal culture, which we view as “best”) rather than considering it from the point of view of those who live and operate within that culture. Cultural relativism is a term used by anthropologists to describe the idea that cultures, because each is unique, can really only be evaluated based on the standards and values of that particular culture (Skolnik, 2021, p. 101). Cultural relativism encourages the attitude that no single culture is better or worse than another, they are all just different. Instead of making determinations about the “rightness” or “wrongness” of cultural practices and beliefs, we should be more concerned with evaluating how well the cultural system meets the physical and psychological health related needs of those whose behavior and attitudes it guides (Skolnik, 2021).

This can be a challenge in global health because while there are many cultural practices, values, or beliefs that can promote better health, there are others that can be harmful to health (according to epidemiological evidence). So, what should be done from the perspective of a health professional who is a cultural outsider when a cultural belief or practice negatively impacts health? What should be done when a behavior is simply different (and therefore seems strange or odd) but doesn’t seem to have any impact on health? In general, it is best to leave such neutral practices alone, regardless of how different they are from our own experiences and beliefs. It is most important to understand and work to modify only practices and values that are clearly harmful. Typically, there are values within a culture that are also supportive of health. As much as possible, such cultural values should be emphasized and incorporated into health programs and policies. Effective health policies and programs depend on being sensitive to local cultures and engaging with those inside the culture to identify initiatives that can improve health in a particular cultural context (Skolnik, 2021).

All public health professionals should strive to develop cultural competence and cultural humility. (Cross, 2012) provides a discussion of cultural competence and its development along a five-point continuum that can be helpful in evaluating one’s level of cultural competence in a particular situation. Though the article discusses agency-level cultural competence, the principles are the same for individuals. There are a number of ways that public health professionals can react to other cultures. These reactions are listed by Cross (2012) in a five-step continuum ranging from destructive to helpful:

- Cultural destructiveness - actively eliminating a different culture.

- Cultural incapacity - not intentionally destructive but unaware of how to help, may use stereotypes and subtly discriminate or patronize.

- Cultural blindness - attempting to be unbiased by treating all cultures the same as the dominant culture, ignoring different perspectives.

- Cultural pre-competence - respecting differences and seeking consultation from minority cultures.

- Cultural competence - holding minority cultures in high esteem, developing approaches desirable to other cultures.

Developing the ability to be respectful, responsive, and open to different cultural groups and beliefs requires intentional, ongoing effort along with self-reflection and awareness. Cultural humility is related to cultural competence, but is a unique concept and one that is critical to success in global health. It has been defined by (Yeager & Bauer-Wu, 2013) as “a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another’s culture, but one starts with an examination of her/his own beliefs and cultural identities. This critical consciousness is more than just self-awareness, but requires one to step back to understand one’s own assumptions, biases, and values…. One cannot understand the makeup and context of others’ lives without being aware and reflective of his/her own background and situation.”

Commercial Determinants of Health

(World Health Organization, 2021b)

Key facts

- Commercial determinants of health are the private sector activities that affect people’s health positively or negatively.

- The private sector influences the social, physical and cultural environments through business actions and societal engagements; for example, supply chains, labor conditions, product design and packaging, research funding, lobbying, preference shaping, and others.

- Commercial determinants of health impact a wide range of health outcomes including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular health, cancer, road traffic injuries, mental health, and malaria.

- Commercial determinants of health affect everyone, but young people are especially at risk, and unhealthy commodities worsen pre-existing economic, social, and racial inequities. Certain countries and regions, such as small island states and low- and middle-income countries, face greater pressure from multinational actors.

- There are effective public health actions to respond to these determinants, which are key to building back better after COVID-19.

Overview

The social determinants of health are the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness. These circumstances are in turn shaped by a wider set of forces: economics, social policies, politics, and the commercial determinants of health. Social determinants of health matter because addressing them not only helps prevent illness, but also promotes healthy lives and societal equity.

Commercial determinants of health are the conditions, actions, and omissions by corporate actors that affect health. Commercial determinants arise in the context of the provision of goods or services for payment and include commercial activities, as well as the environment in which commerce takes place. They can have beneficial or detrimental impacts on health.

Companies shape our physical and social environments

Corporate activities shape the physical and social environments in which people live, work, play, learn, and love – both positively and negatively.

For example:

- Company choices in the production, price-setting, and aggressive marketing of products such as ultra-processed foods, tobacco, sugar-sweetened beverages and alcohol lead to non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, cardiovascular disease, and obesity.

- Young people are especially at risk of being influenced by advertisements and celebrity promotion of material. For example, fast-food advertising to youth activates highly sensitive and still-developing pathways in teens’ brains.

- Mass removal of trees creates mosquito breeding sites, causing vector-borne disease outbreaks like malaria and chikungunya, with up to 20% of malaria risk in deforestation hotspots attributable to international trade of deforestation-implicated export commodities.

- Factories emitting smoke pollute the air, causing and exacerbating respiratory diseases.

- Unsafe or toxic work environments can impact employee mental health.

- Commercial action in knowledge environments can foment inappropriate doubt and thus contribute to scientific denialism. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some governments responded hastily with technologies and interventions that lack scientific evidence of therapeutic effectiveness.

- Intensive animal agriculture is a leading cause of deforestation; antimicrobial resistance; and air, soil, and water pollution. Animal-derived food products are themselves linked to higher rates of noncommunicable diseases, including some cancers and diabetes.

- Workers in slaughterhouses and meat packaging facilities, which are often located in disadvantaged communities, suffer high rates of injury and, at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, experienced high rates of infection from the virus.

However, there are positive contributions by the private sector to public health, for example, when companies implement the following health interventions:

- Reformulation of goods and products to reduce harm and injury, including the industry introduction of seat belts, as well as salt reformulation; and ensuring living wages, paid parental leave to improve child health outcomes, sick leave, and access to health insurance.

The workplace also functions as a setting of health promotion and protection against harm, allowing the following:

- Occupational health and safety standards and hygiene practices that reduce the risk of developing ill-health or work-related disability.

- Health promotion activities aimed at the workforce, including use of stairs, healthy canteens, walkathons or sports events.

- Health literacy events, including awareness building about deadly ailments, blood donation or vaccination.

Commercial determinants drive inequities

Commercial determinants also contribute to other factors that shape health and health equities or the lack thereof. These factors, which have an influence both within and between countries, have a direct impact as well as an indirect impact given that they influence broader economic systems and economic determinants. This includes economic development or trade policies. Examples include:

- Income level

- Educational opportunities

- Occupation, employment status and workplace safety

- Food insecurity and inaccessibility of nutritious food choices

- Access to housing and utility services

- Higher use of tobacco in some regions

- Gender inequity

- Racial segregation

Countries with commodity-dependent economies are especially vulnerable, such as small island developing states and least developing countries. For example, they face greater pressure from industry due to greater employer status or multinational trading agreements.

Private sector influence

Recent decades have seen a transfer of resources to private enterprise, which now plays an increasing role in public health policy and regulation and outcomes. The emergence of non-State actors in the geopolitical arena, together with a shift in global governance, are fundamental to understanding the development of commercial determinants of health. Various authors have cataloged pathways of private sector health strategies and impact, including influencing the political environment, the knowledge environment, and preference shaping.

Corporations commonly influence public health through lobbying and party donations. This incentivizes politicians and political parties to align decisions with commercial agendas. Further, corporations work to capture branches of government to shape their preferred regulatory regime, leading to unregulated activity, limiting their liability and bypassing the threat of litigation and pre-emption.

More subtly, corporations influence the direction, volume of research, and understandings through funding medical education and research, where data may be skewed in favor of commercial interests.

To further shape preferences, corporations capture civil society through corporate front groups, consumer groups, and think tanks, allowing them to manufacture doubt and promote their framings.

Addressing commercial determinants

Partnering with civil society, adopting so-called best buy strategies and conflict of interest policies, and supporting safe spaces for discussions with industry are all examples of how countries can address the commercial determinants of health.

In addition to state capabilities to avoid corruption and steer private sector engagements, more research is needed on the health equity dimensions of commercial determinants of health as well as governance considerations, including transparency and accountability.

Examples of actions governments around the world are taking to address commercial determinants to improve public health include:

- Twenty-nine countries with 832 million people (12% of the world's population) have passed a comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising.

- The United Kingdom has banned junk food advertising online and before 9:00pm on television since 2023.

- Around 50 countries, including France, Brunei Darussalam, Chile, Hungary, India, and Ireland, among others, have charged a tax on sugary soft drinks.

- Saudi Arabia imposed a so-called sin tax in 2017, which levied tax on tobacco products, energy drinks, and soft drinks.

- In Bulgaria, companies give women over 58 weeks of maternity leave on average, which is one of the highest in the world.

- Recovery planning.

There are clear opportunities to move forward on the commercial determinants, particularly in better understanding and addressing the conflicts of interest but also potential co-benefits of private sector action for better health, at global, national, and local levels. The role for transformative partnerships and approaches to achieve the ambitious global health goals was already recognized by the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, but has been brought to the forefront by the COVID-19 pandemic, with increasing attention on the role the private sector plays in health outcomes both within academia and from civil society. This has led to increased scrutiny on the role of the private sector in health and health equity, as well as increasing initiatives within the private sector itself to position itself as a partner.

Environmental Determinants of Health

(World Health Organization, n.d.-a)

Overview

Healthier environments could prevent almost one quarter of the global burden of disease. The COVID-19 pandemic is a further reminder of the delicate relationship between people and our planet.

Clean air, stable climate, adequate water, sanitation and hygiene, safe use of chemicals, protection from radiation, healthy and safe workplaces, sound agricultural practices, health-supportive cities and built environments, and a preserved nature are all prerequisites for good health.

Impact

13.7 million of deaths per year in 2016, amounting to 24% of the global deaths, are due to modifiable environmental risks. This means that almost one in four of total global deaths are linked to environmental conditions.

Disease agents and exposure pathways are numerous and unhealthy environmental conditions are common, with the result that most disease and injury categories are being impacted. Noncommunicable diseases, including ischaemic heart disease, chronic respiratory diseases and cancers are the most frequent disease outcomes caused. Injuries, respiratory infections, and stroke follow closely.

Environmental Determinants of Health

(Pan American Health Organization, n.d.)

A healthy environment is vital to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”

Environmental public health addresses global, regional, national, and local environmental factors that influence human health, including physical, chemical, and biological factors external to a person, and all related behaviors. Collectively, these conditions are referred to as environmental determinants of health (EDHs).

Threats to any one of the EDHs can have an adverse impact on health and well-being at the population level. These environmental threats can occur naturally or because of social conditions and ways people live. Addressing EDHs directly improves the health of populations. Indirectly, it also improves productivity and increases the enjoyment of consumption of goods and services unrelated to health

Key facts

- Approximately 83 million people still do not have adequate sanitation systems of which 15.6 million people still practice open defecation and 28 million do not have access to improve sources of safe drinking water, resulting in about 30 thousand preventable deaths each year.

- Hazardous chemical risks, such as exposure to toxic pesticides, lead, and mercury tend to disproportionately impact children and pregnant women.

- Exposure to toxic chemicals can lead to chronic and often irreversible health conditions such as neurodevelopmental problems, and congenital defects and diseases associated with endocrine disruption.

- Environmental changes such as climate change increasingly have an impact on people’s health and well-being by disrupting physical, biological, and ecological systems globally. Extreme weather events have exacerbated food insecurity, air pollution, access to clean water, population migration and transmission patterns of vector-borne illnesses. The health effects of these disruptions may include increased respiratory, cardiovascular, and infectious disease; injuries; heat stress and mental health problems.

- Groups in situations of vulnerability to climate-related hazards, such as those living on small islands, are subject to a disproportionate risk due to the greater frequency and severity of extreme weather events and the elevation of sea level or communities living in mountains are subject to a disproportionate risk due to changes in river flows, alterations in flora and fauna, and the increased risk of rock landslides, avalanches, and floods due to melting glaciers and decreasing the layer of snow.

- The emergence of new environmental hazards, for example, electronic waste, nanoparticles, microplastics, chemicals that alter the endocrine system, and water scarcity;

- Complex management challenges posed by interregional pollution (for example, cross-border air pollution and shared polluted basins).

Fact sheet

Five key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda address the environmental determinants of health and contribute directly and indirectly to SDG 3 focused on health - ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages. These SDGs address the issues of water, sanitation and hygiene, air quality, chemical safety, and climate action.

To achieve these objectives, environmental public health programs must evaluate possible health problems attributable to environmental factors; develop inclusive and equitable public policies to protect all people from environmental hazards; and ensure compliance with these policies. This is achieved through inter programmatic, intersectoral, multisectoral, subnational, national and supranational approaches. It is important that environmental public health programs foster an environmentally responsible and resilient health sector and environmentally healthy and resilient communities.

Access the appendix for a description of the image.

Drinking Water

(World Health Organization, 2022a)

21 March 2022

Key facts

- Over 2 billion people live in water-stressed countries, which is expected to be exacerbated in some regions as a result of climate change and population growth.

- Globally, at least 2 billion people use a drinking water source contaminated with feces. Microbial contamination of drinking-water as a result of contamination with feces poses the greatest risk to drinking-water safety.

- While the most important chemical risks in drinking water arise from arsenic, fluoride or nitrate, emerging contaminants such as pharmaceuticals, pesticides, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and microplastics generate public concern.

- Safe and sufficient water facilitates the practice of hygiene, which is a key measure to prevent not only diarrhoeal diseases, but acute respiratory infections and numerous neglected tropical diseases.

- Microbiologically contaminated drinking water can transmit diseases such as diarrhea, cholera, dysentery, typhoid, and polio and is estimated to cause 485,000 diarrhoeal deaths each year.

- In 2020, 74% of the global population (5.8 billion people) used a safely managed drinking-water service – that is, one located on premises, available when needed, and free from contamination.

Overview

Safe and readily available water is important for public health, whether it is used for drinking, domestic use, food production, or recreational purposes. Improved water supply and sanitation, and better management of water resources, can boost countries’ economic growth and can contribute greatly to poverty reduction.

In 2010, the UN General Assembly explicitly recognized the human right to water and sanitation. Everyone has the right to sufficient, continuous, safe, acceptable, physically accessible, and affordable water for personal and domestic use.

Drinking-water services

Sustainable Development Goal target 6.1 calls for universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water. The target is tracked with the indicator of safely managed drinking water services – drinking water from an improved water source that is located on premises, available when needed, and free from fecal and priority chemical contamination.

In 2020, 5.8 billion people used safely managed drinking-water services – that is, they used improved water sources located on premises, available when needed, and free from contamination. The remaining 2 billion people without safely managed services in 2020 included:

- 1.2 billion people with basic services, meaning an improved water source located within a round trip of 30 minutes.

- 282 million people with limited services, or an improved water source requiring more than 30 minutes to collect water.

- 368 million people taking water from unprotected wells and springs; and

- 122 million people collecting untreated surface water from lakes, ponds, rivers, and streams.

Sharp geographic, sociocultural, and economic inequalities persist, not only between rural and urban areas but also in towns and cities where people living in low-income, informal, or illegal settlements usually have less access to improved sources of drinking-water than other residents.

Water and health

Contaminated water and poor sanitation are linked to transmission of diseases such as cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid, and polio. Absent, inadequate, or inappropriately managed water and sanitation services expose individuals to preventable health risks. This is particularly the case in health care facilities where both patients and staff are placed at additional risk of infection and disease when water, sanitation, and hygiene services are lacking. Globally, 15% of patients develop an infection during a hospital stay, with the proportion much greater in low-income countries.

Inadequate management of urban, industrial, and agricultural wastewater means the drinking-water of hundreds of millions of people is dangerously contaminated or chemically polluted. Natural presence of chemicals, particularly in groundwater, can also be of health significance, including arsenic and fluoride, while other chemicals, such as lead, may be elevated in drinking-water as a result of leaching from water supply components in contact with drinking-water.

Some 829,000 people are estimated to die each year from diarrhea as a result of unsafe drinking-water, sanitation and hand hygiene. Yet diarrhea is largely preventable, and the deaths of 297,000 children aged under five years could be avoided each year if these risk factors were addressed. Where water is not readily available, people may decide handwashing is not a priority, thereby adding to the likelihood of diarrhea and other diseases.

Diarrhea is the most widely known disease linked to contaminated food and water but there are other hazards. In 2017, over 220 million people required preventative treatment for schistosomiasis – an acute and chronic disease caused by parasitic worms contracted through exposure to infested water.

In many parts of the world, insects that live or breed in water carry and transmit diseases such as dengue fever. Some of these insects, known as vectors, breed in clean water, rather than dirty water. Household drinking water containers can also serve as vector breeding grounds. The simple intervention of covering water storage containers can reduce vector breeding and may also reduce fecal contamination of water at the household level.

Economic and social effects

When water comes from improved and more accessible sources, people spend less time and effort physically collecting it, meaning they can be productive in other ways. This can also result in greater personal safety and reducing musculoskeletal disorders by reducing the need to make long or risky journeys to collect and carry water. Better water sources also mean less expenditure on health, as people are less likely to fall ill and incur medical costs and are better able to remain economically productive.

With children particularly at risk from water-related diseases, access to improved sources of water can result in better health, and therefore better school attendance, with positive longer-term consequences for their lives.

Challenges

Historical rates of progress would need to double for the world to achieve universal coverage with basic drinking water services by 2030. To achieve universal safely managed services, rates would need to quadruple. Climate change, increasing water scarcity, population growth, demographic changes, and urbanization already pose challenges for water supply systems. Over 2 billion people live in water-stressed countries, which is expected to be exacerbated in some regions as a result of climate change and population growth. Reuse of wastewater to recover water, nutrients or energy is becoming an important strategy. Increasingly, countries are using wastewater for irrigation; in developing countries this represents 7% of irrigated land. While this practice if done inappropriately poses health risks, safe management of wastewater can yield multiple benefits, including increased food production.

Options for water sources used for drinking-water and irrigation will continue to evolve, with an increasing reliance on groundwater and alternative sources, including wastewater. Climate change will lead to greater fluctuations in harvested rainwater. Management of all water resources will need to be improved to ensure provision and quality.

Sanitation

(World Health Organization, 2022b)

21 March 2022

Key facts

- In 2020, 54% of the global population (4.2 billion people) used a safely managed sanitation service.

- Over 1.7 billion people still do not have basic sanitation services, such as private toilets or latrines.

- Of these, 494 million still defecate in the open, for example in street gutters, behind bushes or into open bodies of water.

- In 2020, 45% of the household wastewater generated globally was discharged without safe treatment.

- At least 10% of the world’s population is thought to consume food irrigated by wastewater.

- Poor sanitation reduces human well-being, social and economic development due to impacts such as anxiety, risk of sexual assault, and lost opportunities for education and work.

- Poor sanitation is linked to transmission of diarrhoeal diseases such as cholera and dysentery, as well as typhoid, intestinal worm infections and polio. It exacerbates stunting and contributes to the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

Overview

Some 829,000 people in low- and middle-income countries die as a result of inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene each year, representing 60% of total diarrhoeal deaths. Poor sanitation is believed to be the main cause in some 432,000 of these deaths and is a major factor in several neglected tropical diseases, including intestinal worms, schistosomiasis, and trachoma. Poor sanitation also contributes to malnutrition.

In 2020, 54% of the global population (4.2 billion people) used a safely managed sanitation service; 34% (2.6 billion people) used private sanitation facilities connected to sewers from which wastewater was treated; 20% (1.6 billion people) used toilets or latrines where excreta were safely disposed of in situ; and 78% of the world’s population (6.1 billion people) used at least a basic sanitation service.

Diarrhea remains a major killer, but it is largely preventable. Better water, sanitation, and hygiene could prevent the deaths of 297,000 children aged under five years each year from diarrhea.

Open defecation perpetuates a vicious cycle of disease and poverty. The countries where open defecation is most widespread have the highest number of deaths of children aged under five years, as well as the highest levels of malnutrition and poverty, and big disparities of wealth.

Benefits of improving sanitation

Benefits of improved sanitation extend well beyond reducing the risk of diarrhea. These include:

- Reducing the spread of intestinal worms, schistosomiasis and trachoma, which are neglected tropical diseases that cause suffering for millions.

- Reducing the severity and impact of malnutrition.

- Promoting dignity and boosting safety, particularly among women and girls.

- Promoting school attendance: girls’ school attendance is particularly boosted by the provision of separate sanitary facilities.

- Reducing the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

- Potential recovery of water, renewable energy and nutrients from fecal waste.

- Potential to mitigate water scarcity through safe use of wastewater for irrigation especially in areas most affected by climate change.

A WHO study in 2012 calculated that for every US$1.00 invested in sanitation, there was a return of US$5.50 in lower health costs, more productivity, and fewer premature deaths.

Challenges

In 2013, the UN Deputy Secretary-General issued a call to action on sanitation that included the elimination of open defecation by 2025. The world is on track to eliminate open defecation by 2030, if not by 2025, but historical rates of progress would need to double for the world to achieve universal coverage with basic sanitation services by 2030. To achieve universal safely managed services, rates would need to quadruple.

The situation of the urban poor poses a growing challenge as they live increasingly in cities where sewerage is precarious or non-existent, and space for toilets and removal of waste is at a premium. Inequalities in access are compounded when sewage removed from wealthier households is discharged into storm drains, waterways, or landfills, polluting poor residential areas. Globally, approximately half of all wastewater is discharged partially treated or untreated directly into rivers, lakes, or the ocean.

Wastewater is increasingly seen as a resource providing reliable water and nutrients for food production to feed growing urban populations. Yet this requires regulatory oversight and public education. Inadequately treated wastewater is estimated to be used to irrigate croplands in peri-urban areas covering approximately 36 million hectares (equivalent to the size of Germany).

In 2019 UN-Water launched the SDG6 global acceleration framework (GAF). On World Toilet Day 2020, WHO and UNICEF launched the state of the world’s sanitation report laying out the scale of the challenge in terms of health impact, sanitation coverage, progress, policy, investment, and also laying out an acceleration agenda for sanitation under the GAF.

Household air pollution

(World Health Organization, 2022c)

Key facts

- Around 2.4 billion people worldwide (around a third of the global population) cook using open fires or inefficient stoves fuelled by kerosene, biomass (wood, animal dung and crop waste), and coal, which generates harmful household air pollution.

- Household air pollution was responsible for an estimated 3.2 million deaths per year in 2020, including over 237,000 deaths of children under the age of five years.

- The combined effects of ambient air pollution and household air pollution are associated with 6.7 million premature deaths annually.

- Household air pollution exposure leads to noncommunicable diseases including stroke, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and lung cancer.

- Women and children, typically responsible for household chores such as cooking and collecting firewood, bear the greatest health burden from the use of polluting fuels and technologies in homes.

- It is essential to expand use of clean fuels and technologies to reduce household air pollution and protect health. These include solar, electricity, biogas, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), natural gas, alcohol fuels, as well as biomass stoves that meet the emission targets in the WHO Guidelines.

Overview

Worldwide, around 2.4 billion people still cook using solid fuels (such as wood, crop waste, charcoal, coal and dung) and kerosene in open fires and inefficient stoves. Most of these people are poor and live in low- and middle-income countries. There is a large discrepancy in access to cleaner cooking alternatives between urban and rural areas: in 2020, only 14% of people in urban areas relied on polluting fuels and technologies, compared with 52% of the global rural population.

Household air pollution is generated by the use of inefficient and polluting fuels and technologies in and around the home that contains a range of health-damaging pollutants, including small particles that penetrate deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream. In poorly ventilated dwellings, indoor smoke can have levels of fine particles 100 times higher than acceptable. Exposure is particularly high among women and children, who spend the most time near the domestic hearth. Reliance on polluting fuels and technologies also require significant time for cooking on an inefficient device, and gathering and preparing fuel.

Guidance

In light of the widespread use of polluting fuels and stoves for cooking, WHO issued the Guidelines for indoor air quality: household fuel combustion, which offer practical evidence-based guidance on what fuels and technologies used in the home can be considered clean. The Guidelines also include recommendations discouraging use of kerosene and recommending against use of unprocessed coal; specify the performance of fuels and technologies (in the form of emission rate targets) needed to protect health; and emphasize the importance of addressing all household energy uses, particularly cooking, space heating and lighting to ensure benefits for health and the environment. WHO defines fuels and technologies that are clean for health at the point of use as solar, electricity, biogas, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), natural gas, alcohol fuels, as well as biomass stoves that meet the emission targets in the WHO Guidelines.

Without strong policy action, 2.1 billion people are estimated to still lack access to clean fuels and technologies in 2030. There is a particularly critical need for action in sub-Saharan Africa, where population growth has outpaced access to clean cooking, and 923 million people lacked access in 2020. Strategies to increase the adoption of clean household energy include policies that provide financial support to purchase cleaner technologies and fuels, improved ventilation or housing design, and communication campaigns to encourage clean energy use.

Impacts on health

Each year, 3.2 million people die prematurely from illnesses attributable to the household air pollution caused by the incomplete combustion of solid fuels and kerosene used for cooking (see household air pollution data for details). Particulate matter and other pollutants in household air pollution inflame the airways and lungs, impair immune response and reduce the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

Among these 3.2 million deaths from household air pollution exposure:

- 32% are from ischemic heart disease: 12% of all deaths due to ischemic heart disease, accounting for over a million premature deaths annually, can be attributed to exposure to household air pollution.

- 23% are from stroke: approximately 12% of all deaths due to stroke can be attributed to the daily exposure to household air pollution arising from using solid fuels and kerosene at home.

- 21% are due to lower respiratory infection: exposure to household air pollution almost doubles the risk for childhood LRI and is responsible for 44% of all pneumonia deaths in children less than 5 years old. Household air pollution is a risk for acute lower respiratory infections in adults and contributes to 22% of all adult deaths due to pneumonia.

- 19% are from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): 23% of all deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in adults in low- and middle-income countries are due to exposure to household air pollution.

- 6% are from lung cancer: approximately 11% of lung cancer deaths in adults are attributable to exposure to carcinogens from household air pollution caused by using kerosene or solid fuels like wood, charcoal or coal for household energy needs.

- Household air pollution accounted for the loss of an estimated 86 million healthy life years in 2019, with the largest burden falling on women living in low- and middle-income countries.

Almost half of all deaths due to lower respiratory infection among children under five years of age are caused by inhaling particulate matter (soot) from household air pollution.

There is also evidence of links between household air pollution and low birth weight, tuberculosis, cataract, nasopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers.

Impacts on health equity, development and climate change

Significant policy changes are needed to rapidly increase the number of people with access to clean fuels and technologies by 2030 to address health inequities, achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and mitigate climate change.

- Women and children disproportionately bear the greatest health burden from polluting fuels and technologies in homes as they typically labor over household chores such as cooking and collecting firewood and spend more time exposed to harmful smoke from polluting stoves and fuels.

- Gathering fuel increases the risk of musculoskeletal injuries and consumes considerable time for women and children – limiting education and other productive activities. In less secure environments, women and children are at risk of injury and violence while gathering fuel.

- Many of the fuels and technologies used by households for cooking, heating and lighting present safety risks. The ingestion of kerosene by accident is the leading cause of childhood poisonings, and a large fraction of the severe burns and injuries occurring in low- and middle-income countries are linked to household energy use for cooking, heating and lighting.

- The lack of access to electricity for over 750 million people forces households to rely on polluting devices and fuels, such as kerosene lamps for lighting, thus making them exposed to very high levels of fine particulate matter.

- The time spent using and preparing fuel for inefficient, polluting devices limits other opportunities for health and development, like studying, leisure time, or productive activities.

- Black carbon (sooty particles) and methane emitted by inefficient stove combustion are powerful short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs).

- Household air pollution is also a major contributor to ambient (outdoor) air pollution.

Climate Change and Health

(World Health Organization, 2021a)

30 October 2021

Key facts

- Climate change affects the social and environmental determinants of health – clean air, safe drinking water, sufficient food, and secure shelter.

- Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250 000 additional deaths per year, from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress.

- The direct damage costs to health (i.e. excluding costs in health-determining sectors such as agriculture and water and sanitation), is estimated to be between USD 2-4 billion/year by 2030.

- Areas with weak health infrastructure – mostly in developing countries – will be the least able to cope without assistance to prepare and respond.

- Reducing emissions of greenhouse gasses through better transport, food and energy-use choices can result in improved health, particularly through reduced air pollution.

Climate change - the biggest health threat facing humanity

Climate change is the single biggest health threat facing humanity, and health professionals worldwide are already responding to the health harms caused by this unfolding crisis.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has concluded that to avert catastrophic health impacts and prevent millions of climate change-related deaths, the world must limit temperature rise to 1.5°C. Past emissions have already made a certain level of global temperature rise and other changes to the climate inevitable. Global heating of even 1.5°C is not considered safe, however; every additional tenth of a degree of warming will take a serious toll on people’s lives and health.

While no one is safe from the risks of climate change, the people whose health is being harmed first and worst by the climate crisis are the people who contribute least to its causes, and who are least able to protect themselves and their families against it. These are people in low-income and disadvantaged countries and communities.

The climate crisis threatens to undo the last fifty years of progress in development, global health, and poverty reduction, and to further widen existing health inequalities between and within populations. It severely jeopardizes the realization of universal health coverage (UHC) in various ways – including by compounding the existing burden of disease and by exacerbating existing barriers to accessing health services, often at the times when they are most needed. Over 930 million people - around 12% of the world’s population - spend at least 10% of their household budget to pay for health care. With the poorest people largely uninsured, health shocks and stresses already currently push around 100 million people into poverty every year, with the impacts of climate change worsening this trend.

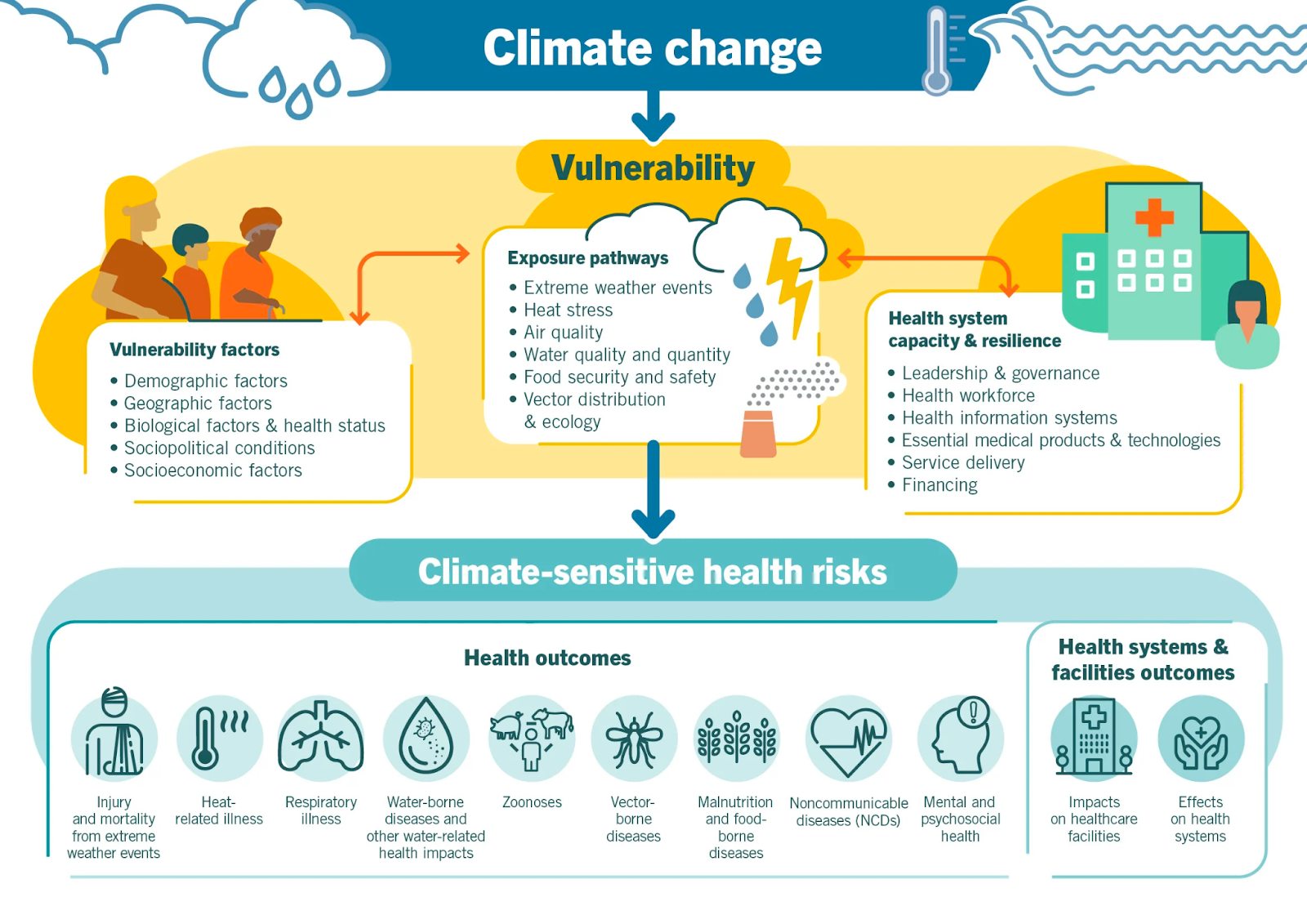

Climate-sensitive health risks

Climate change is already impacting health in a myriad of ways, including by leading to death and illness from increasingly frequent extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, storms, floods; the disruption of food systems; increases in zoonoses and food-, water-, and vector-borne diseases; and mental health issues. Furthermore, climate change is undermining many of the social determinants for good health, such as livelihoods, equality and access to health care and social support structures. These climate-sensitive health risks are disproportionately felt by the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, including women, children, ethnic minorities, poor communities, migrants or displaced persons, older populations, and those with underlying health conditions.

Although it is unequivocal that climate change affects human health, it remains challenging to accurately estimate the scale and impact of many climate-sensitive health risks. However, scientific advances progressively allow us to attribute an increase in morbidity and mortality to human-induced warming, and more accurately determine the risks and scale of these health threats.

In the short- to medium-term, the health impacts of climate change will be determined mainly by the vulnerability of populations, their resilience to the current rate of climate change and the extent and pace of adaptation. In the longer-term, the effects will increasingly depend on the extent to which transformational action is taken now to reduce emissions and avoid the breaching of dangerous temperature thresholds and potential irreversible tipping points.

Access the appendix for a description of the image.

References

Cross, T. (2012). Cultural Competence Continuum. Journal of Child and Youth Care Work, 24, 83–85. https://doi.org/10.5195/jcycw.2012.48

Global Health Education and Learning Incubator at Harvard University. (2018). Brief Introduction to the Social Determinants of Health: Teaching Guide. https://s3.amazonaws.com/production.media.gheli.bbox.ly/filer_public/a3/cf/a3cfedff-de4c-4d6c-91df-1a8fb069e913/2018_gheli_socdet_tchguide.pdf

Pan American Health Organization. (n.d.). Environmental Determinants of Health. PAHO. https://www.paho.org/en/topics/environmental-determinants-health

Skolnik, R. L. (2021). Global Health 101 (4th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

World Health Organization. (n.d.-a). Environmental health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/environmental-health#tab=tab_3

World Health Organization. (n.d.-b). Social determinants of health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization. (2017, February 3). Determinants of health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/determinants-of-health

World Health Organization. (2021a, October 30). Climate change and health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

World Health Organization. (2021b, November 5). Commercial determinants of health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/commercial-determinants-of-health

World Health Organization. (2022a, March 21). Drinking-water. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water

World Health Organization. (2022b, March 21). Sanitation. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sanitation

World Health Organization. (2022c, November 28). Household air pollution. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/household-air-pollution-and-health#:~:text=The%20combined%20effects%20of%20ambient,(COPD)%20and%20lung%20cancer

Yeager, K. A., & Bauer-Wu, S. (2013). Cultural humility: Essential foundation for clinical researchers. Applied Nursing Research, 26(4), 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2013.06.008

Yildiz, S., Toruner, E., & Altay, N. (2018). Effects of different cultures on child health. J Nurs Res Pract, 2(2), 6–10.

This content is provided to you freely by BYU-I Books.

Access it online or download it at https://books.byui.edu/pubh_480_readings/chapter_2_determinan.